The education of Michelle Shocked

Once portrayed as a bumpkin, she's finally wised up

Michelle Shocked doesn’t get back to Dallas much anymore. She lives in New Orleans now, and though she lives in a state bordering Texas, she resides just far enough from her old home that she doesn’t much think about Texas anymore – except, maybe, when she writes a song. But even then, the influences exist only in her subconscious. Shocked is tied to Texas by music, but not much else.

Shocked used to visit Texas a lot, usually to see her father in Dallas, a mandolin player named “Dollar Bill” Johnston who had a profound impact upon his young daughter. Dollar Bill used to take his young daughter, Michelle, and her brother, Wilco’s Max Johnston, to bluegrass festivals around the country, and it was there that she picked up the folk and country sounds that would mark her best work. But Shocked says she has not been back to Texas in two years, since her last tour through these parts, and she doesn’t much keep in contact with her father anymore.

“I’m not on good terms with him,” she explains in a deadpan voice. Shocked’s mother, who was divorced from Dollar Bill when Michelle was a kid, once committed Michelle to a Dallas psychiatric hospital 12 years ago. Michelle stayed there till the insurance money ran out, then she left home and never looked back except to see her father. Now, she has removed the rearview mirror altogether. “My father invited my mother to the hospital when my grandmother died, and I thought that was pretty insensitive.”

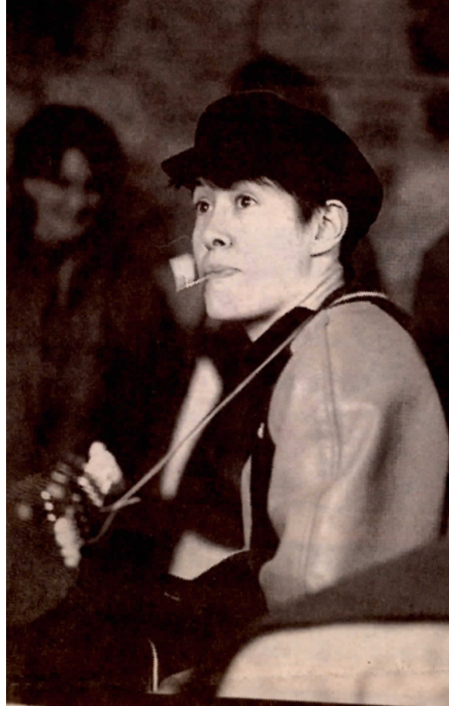

Such are the prices of growing up – in private, and in a music business that demands full disclosure from its practitioners. Shocked is no longer the same young woman whose first album was released without her knowledge almost a decade ago, nor is she the same would-be Woody Guthrie traveling the land with her acoustic guitar and short, sharp haircut singing of desolate lands and desolate souls.

She has gotten off her major label and become an independent in every sense of the word, taken control of a career she once allowed others to direct, assumed ownership of her own songs after leaving them for so long in the hands of others. And even more to the point, the folkie has gone funk, hiring old Motown session men for her track, “Quality of Mercy,” on the Dead Man Walking soundtrack and whatever album she might end up doing next.

For so long, Shocked was portrayed in the press as a hillbilly, a simple country girl who wrote pointed country-folk songs about a hard land in hard times. When The Texas Campfire Tapes was released in 1986, writers often repeated the same story of how she recorded the songs on a fan’s weak-batteried Walkman only to find out the fan, British record-label owner Pete Lawrence, had released them in England to critical acclaim and commercial success. Shocked was living on the verge of homelessness in New York City, where she worked as a squatters’ activist, when she discovered the album had reached the top of the British indie charts.

No one ever bothered to ask if Shocked got any money from the record, or if the label had her permission to release the tapes in the first place. It’s part of her untold story that she had to sue Lawrence for the rights to her songs, and it was only the first arduous and painful legal battle she would endure during the course of her relatively short career. Now, Shocked refers to The Texas Campfire Tapes as The Texas Campfire Thefts, and though she owns the rights, she’d rather they not remain in print.

“It was a lawsuit that caused this very bitter attitude on my part, which is where I picked up the term ‘Texas Campfire Thefts,’” she says. “That was settled out of court eventually, but I went through a real seven-year English, powdered-wig, m’lord-m’lady kind of legal battle, and it was hard. Now, it feels like a tremendous opportunity to rewrite this history of exploitation. It’s like reclaiming history for those who have been exploited, and it’s a real victory, but it was draining.”

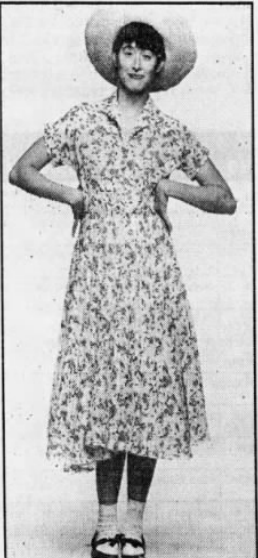

Throughout the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, rock journalists painted Shocked as an innocent at home, and they treated her much as writers treated Leadbelly [sic] when he was “rescued” from poverty and prison by musicologist plunderer Alan Lomax—almost as a freak behind thin glass, there to be ogled by the smart white city folk who file by. Articles that coincided with the releases of Short Sharp Shocked in 1988 and Captain Swing in 1989 read almost exactly the same, even as the music grew from bare-bones folk to larger-than-life swing.

She remained the waiflike Texan who ran away from home, traveled the world with the homeless and the derelict, then came home to rediscover her roots. She was Guthrie traveling the hard land with a guitar and a notebook, singing her diaries. She was the protesting folkie who landed in jail protesting the injustices of the world. She was a symbol.

“Before, the story was so perfect and pat,” Shocked says of her earliest days in the music business. “It’s a lot of marketing, having a myth or a story to kind of get people interested. There were obvious contradictions to it—a name like Michelle Shocked, the punk hairdo, all these big-mouth political things. The only thing I ever saw that approached it was when someone asked, ‘How can this rootless girl be such a representative of roots music?’”

Of course, Shocked didn’t help her cause much. In fact, she went out of her way to foster her hick-chanteuse image, penning her own record-label bios by hand and imbuing them with a good-ol’-gal sensibility that would endear her to the good-ol’boy rock establishment. If her songs were clear-eyed reflections of a physical landscape (Texas, for the most part, a land you can’t escape even if you’re in Amsterdam) and an emotional terrain (Shocked has spoken openly about being sexually abused while abroad), then her bios were a fun-house mirror reflection of the performer.

“It’s like I told those journalist fellows in London who wanted to make interviews with me,” she wrote in the bio for Short Sharp Shocked. “I don’t know what all the fuss is about, and if you like it so much, well, there’s plenty more where I came from.”

It never occurred to writers that Shocked’s two personas clashed like stripes and polka dots, and they rarely tried to find the real woman inside the overalls. She was either the screaming woman depicted on the cover of Short Sharp Shocked in that now-famous photo of her getting dragged away kicking and screaming by the San Francisco cops outside the 1984 Democratic National Convention, or she was the chick hick from the sticks. You couldn’t be both, no damned way.

“I contributed to that early on, and some of it was because I was naïve, but some of it was savvy,” she says now. “Being a student both of Marshall McLuhan and Abbie Hoffman, I had a pretty strong understanding that first impressions last, and so, on the cover of Short Sharp Shocked, to use a photo like that – for the type of material on that record was a paradox. It was incongruous.

“But I ended up feeling like, if people are going to end up remembering me for an image, I would rather it be something rebellious and kind of gritty than some-me-holding-an-acoustic-guitar-with-warm-wooden-tones album cover with me looking sensitively down at my shoes. I was willing to accept that on one level but fighting against it in the meantime has not been something I’ve proven very adept at. I’ve had to rely on Bart a lot for that, I suppose.”

The “Bart” to whom she refers is Bart Bull, a rock writer who met and fell in love with Shocked when he went to interview her seven years ago. Cynics have long pushed the theory that Bull is sort of Shocked’s Svengali, that he somehow has influenced her career and kept her from recording. (Her last major release was 1992’s Arkansas Traveler, a hodgepodge recorded with various musicians all over the country including her father and brother, Uncle Tupelo, Pops Staples, and Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown.)

Shocked actually shot herself in the foot (and leg, and hand, etc.) at the South by Southwest music conference in Austin when, in 1992, she delivered a keynote address written by Bull. Taken from his rambling “work in progress” about blackface minstrelsy (titled “Does This Road Go to Little Rock?), her speech was a disjointed, often bizarre series of points connected by the theme that white people have been ripping off the music of the African-American for years. (Yeah, and…?) By the end of her monologue, people were actually standing outside the ballroom laughing at Shocked, so sure she just didn’t get what she was talking about, especially after she ripped into Fishbone for playing to white audiences. (Yeah; so…?)

To make matters worse, at the last minute Shocked attempted to kick Two Nice Girls off a benefit concert scheduled during the conference – something to do with her being “uncomfortable,” said Shocked’s then-manager at the time. The Queer Nation took this as a slap to Two Nice Girls’ overtly lesbian stance and promptly posted fliers all over Sixth Street reading, “Michelle, We’re Shocked.” As a kicker, Shocked fired the Bad Livers as her backup band the day of the benefit performance, which is akin to heresy in Austin.

Those who attended SXSW were sure Shocked had killed her career on the spot, and when she released [Arkansas] Traveler shortly after that, it received significantly less critical attention than her previous records – despite it being a terrific, inspired piece of work. Yet it was all part of the process of maturing, discovering fame isn’t a gold card with which you collect frequent asshole miles. To talk to her now is to talk to a woman who figured out where she went wrong and how she got right.

Shocked just recently received her release from Mercury Records, though the process was an arduous one that involved considerable litigation. In the end, she had to sue using the post-Civil War 13th Amendment as her legal sword, claiming the record label was holding her hostage – or more to the point, using her as a slave.

She claims she wanted off the label because Mercury executives weren’t going to allow her to release the records she wanted to make (a funk record, of all things), and she refused to give them the sensitive-girl-with-an-acoustic-guitar record they insisted she turn in. It was a stalemate, and the battle became ugly.

In the end, Shocked’s fourth album, 1994’s Kind Hearted Woman, never saw the fluorescent light of a record store; instead, Shocked sold the disc only at her concerts. It’s actually not a complete record, but a sparse sketch of one that’s not so different from Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska; she has, however, re-recorded it with members of Hothouse Flowers, fleshing it out with larger arrangements.

Now, she has to decide whether to release it herself, license it as a one-off deal to a distributor or label, or make it the first record of a new deal with another label. But she is in no hurry to buy back into a system that tried to sell her out, so she waits patiently. She has all the time in the world, and she needs it.

Michelle Shocked performs April 26 at Deep Ellum Live.

Added to Library on April 26, 2020. (132)

Copyright-protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s).